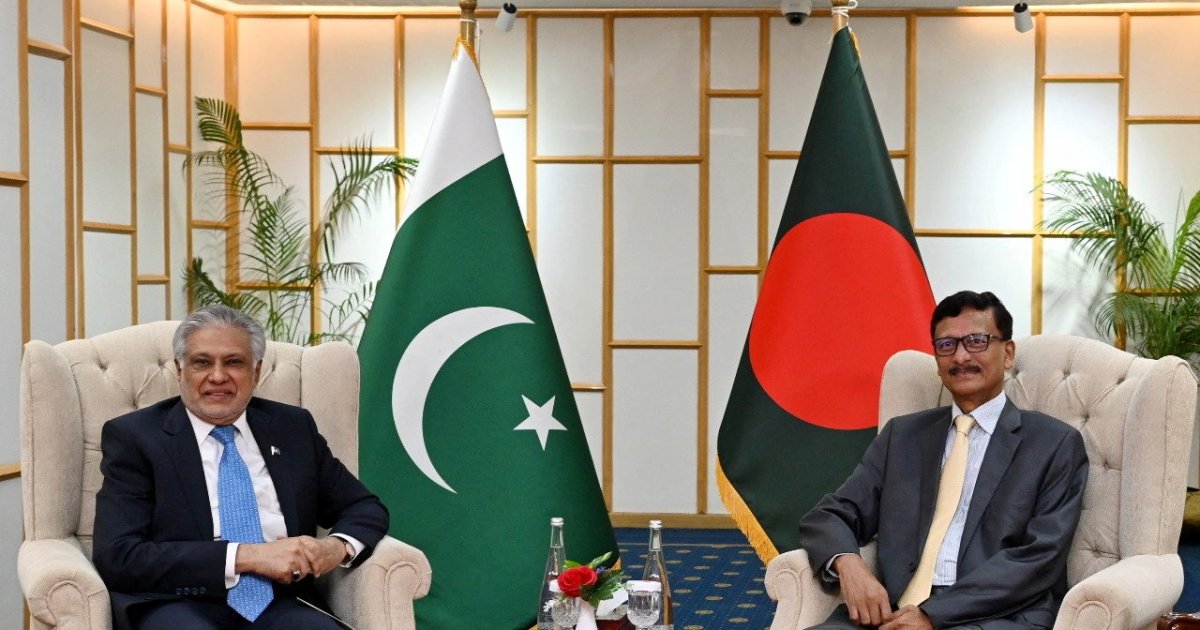

Pakistan Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar has said that a recent trilateral initiative between Bangladesh, China and Islamabad could be “expanded” to include other regional nations and beyond.

“We have opposed … zero-sum approaches and consistently stressed the imperative of cooperation rather than confrontation,” he told the Islamabad Conclave forum on Wednesday.

- list 1 of 3Why India likely won’t return Hasina to face Bangladesh death penalty

- list 2 of 3A Pakistan foreign policy renaissance? Not quite

- list 3 of 3Who are India and Pakistan blaming for Delhi, Islamabad blasts?

end of list

In effect, the proposal amounts to the creation of an alternative bloc focused on South Asia, with China added, at a time when the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) — the region’s main grouping — has been made almost defunct by heightened India-Pakistan tensions in recent years.

In June, diplomats from China, Pakistan and Bangladesh held trilateral talks focusing on regional stability, economic development and enhancing people’s lives, a cooperation they said was “not directed at any third party”.

Dar’s remarks come against a backdrop of escalating regional tensions, including Pakistan’s decades-long rivalry with India. The two nuclear-armed neighbours fought a brief four-day air war in May, further straining relations.

Meanwhile, ties between Dhaka and New Delhi have also deteriorated sharply following the ouster of former Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in August last year. Hasina fled to India after being deposed in a popular uprising, and New Delhi has so far refused to send the former PM back to Bangladesh, where she was convicted by a tribunal in November of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death.

Advertisement

But will most other South Asian nations — SAARC consists of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Maldives, Bhutan and Afghanistan — agree to a new regional grouping that appears aimed at cutting India out, or at least limiting its influence?

Here is what you need to know:

What is Pakistan’s proposal?

Deputy Prime Minister Dar, who is also Pakistan’s foreign minister, said the trilateral initiative with Bangladesh and China aimed to “foster mutual collaboration” in areas of shared interest, and that the concept be “expanded and duplicated” to include more countries and regions.

“As I have said before, there could be groups with variable geometry on issues from economy to technology to connectivity,” he told the conclave in Islamabad.

“Our own national development needs and regional priorities cannot – and should not – be held hostage to anyone’s rigidity, and you know where I am referring to,” he said, in an apparent reference to India.

On tensions between Islamabad and New Delhi, Dar pointed out that a “structured dialogue” process between India and Pakistan has remained in limbo “for over 11 years”, adding that other regional states have had their share of a “seesaw relationship with our neighbour India”.

The foreign minister said Pakistan envisions a South Asia where links and cooperation replace “divisions, economies grow in synergy, disputes are resolved peacefully in accordance with international legitimacy, and where peace is maintained with dignity and honour”.

According to academic Rabia Akhtar, the proposal at this stage is likely “more aspirational than operational”.

“But it signals Pakistan’s intent to diversify and reimagine regional cooperation mechanisms at a time when SAARC remains paralysed,” Akhtar, director at the Centre for Security, Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR) at the University of Lahore, told Al Jazeera.

What is the regional organisation SAARC?

SAARC was established in 1985 at a summit in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Its seven founding members were Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Afghanistan joined to become the eighth member in 2007.

According to its website, the objectives of SAARC include improving the welfare and quality of life of South Asians, generating economic growth and cultural development.

Despite its lofty ambitions, the organisation has struggled to achieve its goals over the past 40 years, in large part due to the decades-long tensions between India and Pakistan, who have fought three full-scale wars since their independence from the British in 1947, which also coincided with the partition of the subcontinent.

Advertisement

The 19th SAARC summit in 2016, scheduled to be hosted by Islamabad, was indefinitely postponed after India pulled out, citing a deadly attack in Indian-administered Kashmir and holding Pakistan responsible.

“The organisation requires consensus to function, and without political willingness from the two largest members to separate regional cooperation from bilateral disputes, SAARC cannot move forward,” CSSPR’s Akhtar said.

The last summit of the regional body was held in 2014 in Kathmandu, Nepal. However, analysts say while SAARC remains dormant, the organisation has potential to deliver for the region — if India and Pakistan allow it to.

Why is SAARC important?

As of 2025, SAARC countries make up more than two billion of the world’s population, making South Asia the world’s most densely populated region.

Yet, trade within South Asia is minimal, representing only about 5 percent of the region’s overall commerce, around $23bn, the World Bank has said. By contrast, trade between member states of ASEAN, a bloc of 11 Southeast Asian nations home to about 700 million people, represents 25 percent of their international commerce, the Washington-based institution noted.

South Asian nations could exchange goods worth $67bn – three times their current trade – if they reduced barriers, the World Bank estimates.

Trade between India and Pakistan, in particular, remains dismal. In the financial year 2017-2018, official trade between the two neighbours stood at a mere $2.41bn. It fell further, halving to $1.2bn by 2024 – though unofficial trade between them, routed through other countries, is larger, at about $10bn, experts say.

Lack of regional connectivity is cited as one major reason for the region’s weak trade links.

In 2014, the grouping was poised to sign a Motor Vehicles Agreement that would have allowed cars and trucks to travel across South Asia, as they can in Europe. But Pakistan blocked that agreement – and a separate one on regional railway collaboration – amid tensions with India.

Since then, the grouping’s ability to come together has been limited to a few occasions, like during the COVID-19 pandemic when member states set up an emergency fund and set aside $7.7bn to help tackle the public health crisis.

“If the two countries [India and Pakistan] were able to identify even limited avenues for cooperation in the service of broader regional interests, SAARC could, in principle, be revived,” analyst Farwa Aamer told Al Jazeera.

“However, given current political dynamics, such a breakthrough appears to be a distant prospect,” Aamer, director of South Asia Initiatives at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), added.

But Pakistan isn’t the first to attempt to sidestep SAARC to build its regional partnerships. After SAARC failed to approve a regional transport pact, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal – in a grouping called the BBIN after the country initials – inked a similar agreement among themselves.

India is also part of other regional organisations like the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), Aamer pointed out. BIMSTEC includes India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

Advertisement

Still, on the whole, Aamer said, “bilateral and trilateral arrangements will continue to dominate” over “regional multilateralism” in the “near to medium term”. That’s because dealing with just one or two countries at a time tends “to offer more flexibility, clearer incentives and a greater likelihood of producing tangible outcomes,” she said.

Will Pakistan’s proposal work?

Whether the proposal works will depend on two factors, academic Akhtar said.

“First, whether prospective states see functional value in smaller, issue-focused groupings at a moment when traditional architectures are stalled; and second, whether participation does not trigger political costs vis-a-vis India.”

Akhtar said several South Asian countries may show tentative interest in Pakistan’s proposed regional initiative, though any move towards formal participation is expected to remain limited.

“I think countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal, the Maldives, and perhaps Bhutan may be open to exploratory engagement, particularly on connectivity, climate adaptation and economic resilience,” she said.

However, Akhtar noted that India’s regional sensitivities and wider geopolitical rivalry with Pakistan and China “mean that actual membership uptake will be cautious”.

Nevertheless, ASPI’s Aamer believes Pakistan’s proposition was a “strategically coherent” one.

“The country is in a moment of diplomatic agility,” she said, adding that “it has maintained strong relations with China while simultaneously cultivating renewed and improved ties with the United States and the Gulf”.

“This dual-track engagement has given Islamabad a sense of confidence and the ambition to reassert itself as a significant regional actor, essentially, to reclaim a seat at the centre of regional diplomacy.”

Related News

US sanctions must be stopped as they reshape life in Cuba: UN rapporteur

Bolsonaro says hallucinatory effects of meds made him tamper with ankle tag

India ‘examining’ Bangladesh extradition request for convicted ex-PM Hasina